First Flight Around the World - 100 Years Later

By Mike Lentes

The year 1924 was a time for aviation to spread its wings in North America. On April 1 of that year, Canada restructured its air services and formed the Royal Canadian Air Force. Just days later, on April 6, the U.S. Army Air Service embarked on its attempt to fly around the world – something many thought to be impossible. Fly around the world? No one had even crossed the Pacific in an “aeroplane” yet.

The U.S. Army Air Service asked the Douglas Airplane Company to build four aircraft that were rugged and capable of long-distance flight. Donald Douglas was a 32-year-old designer and engineer who had founded his company just four years earlier on a $600 shoestring. Although his company wasn’t much more than a startup, his track record was good, and the Air Service had confidence in Douglas despite his youth.

The four aircraft he built were called Douglas World Cruisers and named for U.S. cities – Seattle – Chicago – Boston – and New Orleans. Because of Prohibition, bottles of water instead of champagne were used to christen the aircraft. Water from Lake Washington christened the Seattle – the Chicago was baptized with a bottle of water from Lake Michigan – the Atlantic Ocean supplied water for the Boston – and the New Orleans was doused with water from the Gulf of Mexico.

The flight began at Seattle, where the Boeing Company helped ready the World Cruisers and outfit them with floats. They were both land and seaplanes – a new concept then. Each would be crewed by two pilots with one of them also serving as a skilled mechanic. Both cockpits were open to the weather and equipped with an identical set of controls and instruments. The World Cruisers were flight ready and so were the crews.

The crew of the Chicago – Lt. Lowell Smith and Lt. Les Arnold – recorded their experiences on the World Flight. The quotes in this account of the flight are from their journal, unless otherwise noted. The journal begins:

“We all have confidence in ourselves, or we wouldn’t be here, and just as important, we have faith in our Douglas Cruisers and Liberty motors, confidence in our Air Service, and complete trust in the staff doing our advance work.”

The four Cruisers lifted off from Seattle on the morning of April 6, with the first planned stop 650 miles to the north – Prince Rupert, British Columbia. The crews would soon learn that, on their flight around the world, Mother Nature would oftentimes be an Angry She-devil.

Shortly after leaving Seattle: “Now we are passing through a haze like the smoke from a forest fire. We soon discovered that this haze was the forerunner of a fog which gradually grew thicker and thicker, forcing us to fly lower and lower until we were soon flying only a few feet above the water. Just before we passed into Queen Charlotte Sound, the ceiling lifted to 500 feet, and although we had run into a rainstorm, we could see the Indian settlement at Alert Bay, on the east coast of Vancouver Island. Plunging on through drenching rain, and rounding Cape Caution, we saw the great swells rolling in from thousands of miles across the Pacific. Fully forty or fifty feet high, these cold, gray waves looked to be as I leaned over the edge of the cockpit. I wondered what would happen if we had to flop down in the middle of those angry seas. You can land in fairly rough water, but never in such wild, angry seas as these were.

“Rounding Calvert Island, we swung to the right and sought the shelter of the Inside Passage. From then on there wasn’t a clear stretch of water all the way to Prince Rupert. Sometimes we were flying through driving rain, sometimes through fleecy snow, through sheets of sleet, and twice through squalls of hail that pelted the fuselage and wings like a flock of machine-gun bullets all striking at once.

After an eight-hour flight through weather extremes, they landed at Prince Rupert in a raging snowstorm. Standing in the snow and looking like Father Christmas, the mayor of Prince Rupert greeted them with a warm smile. “Gentlemen, you have arrived on the worst day we’ve had in ten years.” The Journal continues:

“As soon we stepped ashore, the Canadians offered us hot tea and other beverages for which Canada is famous. The people of Prince Rupert gave us an official banquet and many of those who attended were dressed formally. We, on the other hand, had nothing but the heavy woolen shirts and trousers, sweaters, chamois flying-jackets fur-lined coats, and the arctic pack shoes that we wore. It was at this banquet that we passed through one of life’s embarrassing moments, an episode that reminded us of how our educations had been neglected since the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment. When our hosts rose to drink to our success, we innocently made the mistake of standing with them and dumbly drinking a toast to ourselves!”

They remained at Prince Rupert four days, tending to their aircraft while waiting for the weather to improve. “An old fisherman named John Toner used to row us back and forth from the shore to our planes out at Seal Cove. John’s home was a floating shack – a sort of Arctic Noah’s Ark, inhabited by dogs, fish, clams and crabs, and a rendezvous for all of John’s fishermen cronies. Occasionally we would duck into John’s shack to dry our clothing and get warm, and we would sit around his sheet-iron stove listening to him spin yarns while we devoured the crabs and crackers and hot coffee that he prepared for us.” The crews were eager to be on their way and when the weather cleared a bit, they continued up the north Pacific coast. Next stop – Alaska.

It was in Alaska they suffered their first casualty – the Seattle crashed in dense fog on a mountainside and was demolished. The crew escaped with only minor injuries, but they were stranded ten days from nowhere. Their only food supply was some hardtack and a can of beef concentrate which they rationed a teaspoonful at a time in a cup of water. Both men suffered from snow blindness, lack of food and fatigue. The little sleep they did get was an occasional short snooze while sitting in the snow.

After 7 days of hiking, they discovered a trapper’s cabin with no furniture but with a stove and a rifle, which they used to bag a few snowshoe rabbits. Three days later they set out again and after a 20-mile trek through snow and sub-zero temperatures, they spotted a radio mast in the distance with smoke coming from the chimney of a building – a fish cannery. News that they were safe was flashed to their worried families and the other World Cruiser crews. As the Seattle crew later recalled: “The tragedy to us was that, as far as we two were concerned, the World Flight was over.”

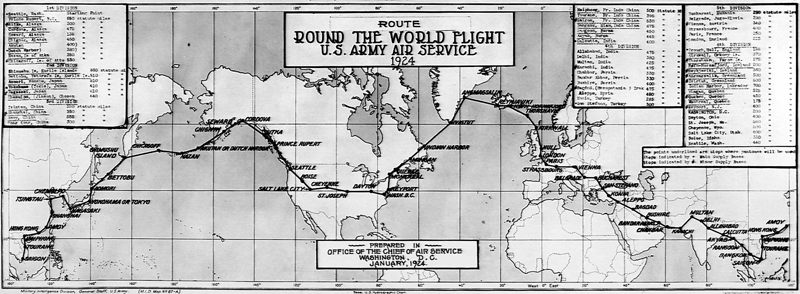

The three remaining Cruisers would continue on their world flight with stops in 28 countries along the way, including Japan – China – French Indochina – Burma – India – Persia – Turkey and six European countries. It was on their homebound leg after departing Europe they were destined to lose another Cruiser. Next challenge – the Atlantic.

While over the Atlantic en route to Iceland, the Boston lost all oil pressure, and the crew was forced to make a sea landing. The Chicago crew saw what happened and went in search of a ship to help the downed aircraft. Luckily, they found the U.S. cruiser Richmond and after three message-bag drops, help was on the way. The Richmond rescued the crew, and the Bostonwas taken in tow but, by nightfall, high seas broke up the aircraft and she sank to the bottom of the Atlantic.

On their way to Iceland, the two surviving aircraft flew over 30-foot swells and a sea dotted with icebergs. At one point, flying side by side, a towering iceberg appeared directly in front of them. The Chicago banked one way and New Orleans the other – both aircraft were lost to each other. From the Chicago flight log: “We simply jerked the wheel back for a quick climb, and we were lucky enough to zoom over the top of it into the still denser fog above. Here we were completely lost and unable to see beyond the prop and the wing tips.” After several hours dodging more icebergs, they reunited in Iceland at Reykjavik.

Their stay in Iceland lasted two weeks because of severe weather in the north Atlantic. Knowing they were in the homestretch, the Chicago and Boston crews were happy to see North America again when they landed in Canada at Icy Tickle, Labrador. They were finally greeted with good flying conditions and stopped in Newfoundland to refuel and service their planes before continuing to Pictou Harbor in Nova Scotia. It was there that a surprise awaited them – they were greeted by a “resurrected” World Cruiser.

Before production of the four World Cruisers, Douglas had built a prototype which was parked at Langley Field in Virginia. When the Army Air Service learned that the Boston had been lost, the prototype was hurriedly flown to Nova Scotia where it met the Chicago and New Orleans. The crew of the original Boston howled like banshees when they learned they would again be part of the flight in their new World Cruiser – the Boston II.

The three Cruisers reached the east coast of the U.S. mainland and were greeted by enthusiastic crowds at 20 cities on the homecoming leg of the flight. The stop at Santa Monica in California was special since the World Cruisers had been built there. As they neared Clover Field, one of the pilots said: “Boy, we’re in for a wild time!” Cars were jammed fender to fender in rows a half-mile long and a half-mile deep. The crowd was estimated at 200,000 and a full acre of freshly cut roses was next to the grandstand that had been built for the occasion. Immediately upon landing, one of the crew jumped out of his cockpit and shouted: “Where’s Donald Douglas? I want to congratulate that boy, for he sure does know how to build airplanes.” Some in the crowd swept past the police and army security to surround the crew. They were hugged, kissed, and pummeled – the price to be paid for fame and glory. Last stop – Seattle.

On September 28, 1924, an animated crowd of 50,000 greeted the weary crews at Sand Point in Seattle where it all began – 175 days earlier. Awaiting them was a telegram from President Coolidge on behalf of the country expressing their congratulations and appreciation. There were other messages from around the world, including one from King George V of England. After 72 stops in 28 countries, they endured and had circled the globe. The flight proved that long-distance flight – and commercial aviation – was indeed possible.

-

Mike Lentes is a pilot and aviation historian. He ranks the Douglas World Cruiser flight as the most unlikely success story since Kitty Hawk. A keen interest in history led to his lifelong collection of unique aviation artifacts, including the original wing fabric from the World Cruiser “Chicago.” His archived collection of the "Chicago" wing fabric is now available to aviation educators and collectors at https://aviationrelics.com/douglas-world-cruiser/ The website is funding CEILING AND VISIBILITY UNLIMITED – a weekend aviation camp for at-risk kids.